Press Releases

Press Releases

Yesterday, the Lords insisted on its amendments to the Safety of Rwanda Bill, only for the Commons to push it back this afternoon, and then for the Lords to push it back once again this evening.

So it’s now the fourth time the Lords has rejected the will of the elected chamber, and it begins to raise serious constitutional questions about the role of the House of Lords.

The House of Lords is not there to block the public will as expressed by the lower house.

The Parliament Act of 1911 was introduced because in an increasingly democratic age – and bear in mind in 1911, there wasn’t universal suffrage, women didn’t have the vote, nor did quite a lot of men.

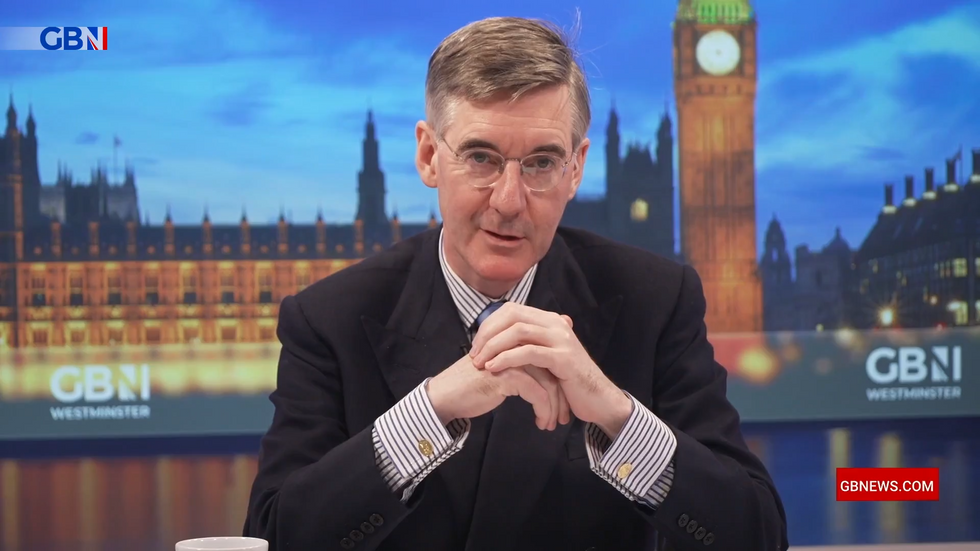

Jacob Rees-Mogg reacts to the House of Lords’s ruling on the Rwanda Bill

GB News

But even then, it was thought the peers had gone too far when, against convention, they rejected Lloyd George’s budget.

After two years of constitutional wrangling, it then had its powers cut down dramatically.

Incidentally, the preamble to the Parliament Act says it’s a temporary measure, and here we are 113 years on and it’s still there.

And reform is a sword of Damocles holding over the chamber that, if it exceeds convention without any mandate, risks being reformed more fundamentally.

And it has evolved over the years, the decades, the centuries to be a reviving chamber; secondary to the Commons, entitled to ask the Commons to think again, but not to block.

Currently, it’s seeking to block by passing wrecking amendments to the Rwanda Bill. The Bill has two main purposes.

One, to declare Rwanda a safe country and two, to dis-apply some aspects of human rights laws where they might otherwise take effect.

The Lords is attacking both of these efforts. One amendment insists that the Safety of Rwanda bill should have due regard for international law. But this merely keeps deportations hostage to the increasingly erratic interventions from the European Court of Human Rights.

Even the issue in relation to the Afghanistanis, or to the committee that would be set up would bring the lawyers back in to undermine what ministers have decided. Another amendment insists on the status of Rwanda being subject to the independent monitoring committee. But Parliament is allowed to declare facts.

Parliament has the right to declare facts and has done since the Tudor period. It is an essential component of the concept of parliamentary sovereignty, which makes the King in Parliament the supreme authority and arbiter in the land on any issue on which it chooses to legislate. In this instance, the bill aims to settle a matter of opinion – Ministers think Rwanda is safe, some judges disagree.

Who should decide? The elected or the unelected? You or the blob? Peers versus the people never ends well for the peers. So they should have backed down earlier today and they must back down next week.

24World Media does not take any responsibility of the information you see on this page. The content this page contains is from independent third-party content provider. If you have any concerns regarding the content, please free to write us here: contact@24worldmedia.com